Editor’s note: This essay was adapted from a submission Doug made last year to the George and Anna Eliot Ticknor Collecting Prize, for which he was awarded Honorable Mention.

by Douglas Scott Brown

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” -Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

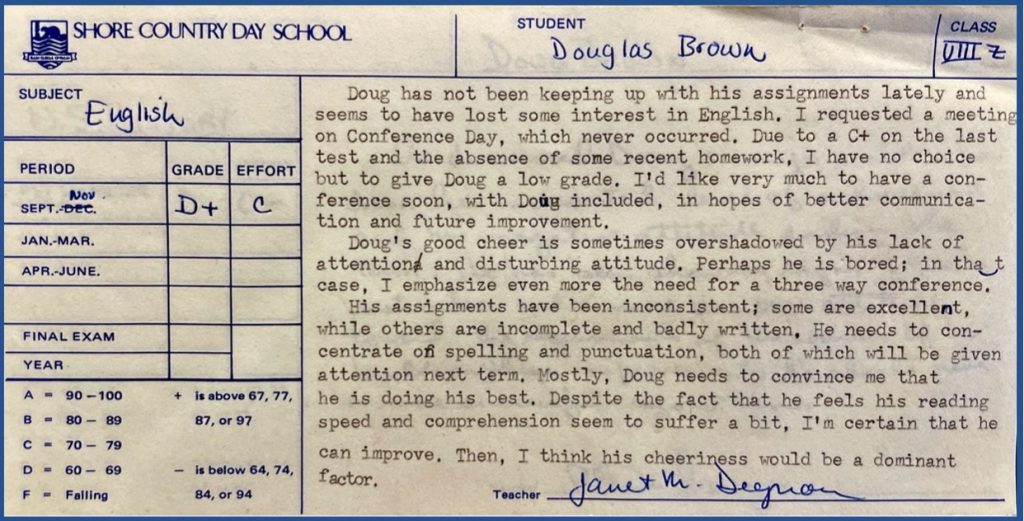

I may be the unlikeliest of rare book collectors. My eighth grade report card from 1976 notes that I lost interest in English class. “Doug’s good cheer is sometimes overshadowed by his lack of attention and disturbing attitude.” Fortunately for me, with the guidance of some kind teachers, I found my way, and would eventually embark on a satisfying career through the law, government and health care. But books, especially old books, were never a big part of my life.

That all changed in 2020. A combination of COVID-19 and the election pulled me unexpectedly and passionately into the world of rare books.

I work for a large health care system in central Massachusetts, and my system was hit especially hard by COVID. It was stressful for all of us. Losing myself in books became my respite. It carried me into history, adventure, and curiosity. It brought me newfound joy.

At a time when the world around me was shutting down, a new and different world was opening up. Through the internet, I discovered I could access the inventories of antiquarian booksellers across the globe right from the comforts of my own home. I met fascinating book people who encouraged my journey, and quenched my thirst for human connection, even if virtual.

My initial focus was in the area of history and government and it was driven by the 2020 election and its aftermath. As a lawyer and student of politics, I had difficulty processing how this undermining of our election could happen in our democracy. It left me with a yearning to get close to the principles upon which our country was founded. I wanted to possess the sources that influenced our Founding Fathers.

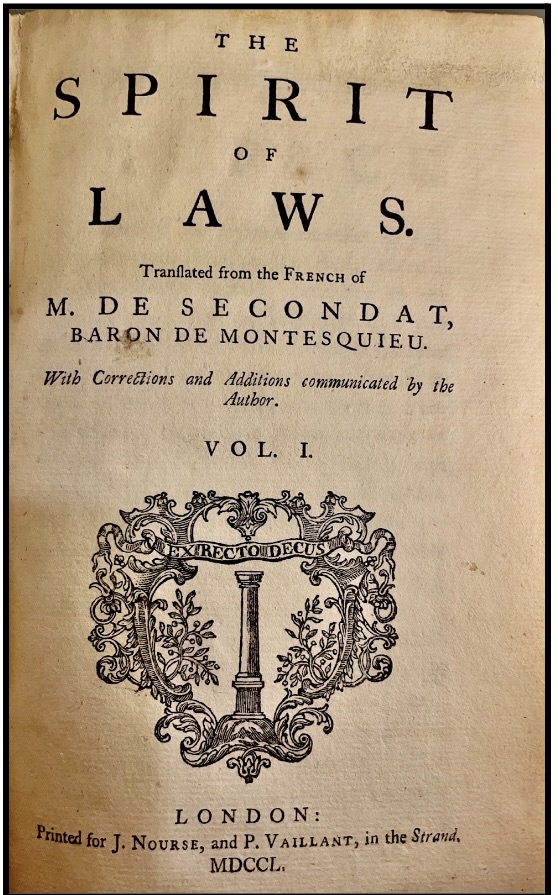

One of my first purchases was The Spirit of the Laws by Montesquieu. I found a first English edition (1750) from a book seller in Germany. Montesquieu articulated the need for “checks and balances” in a democratic government. The work greatly influenced Hamilton and Madison. Owning this book gave me comfort. It was my personal demonstration of support for a government that was built to withstand this kind of crisis.

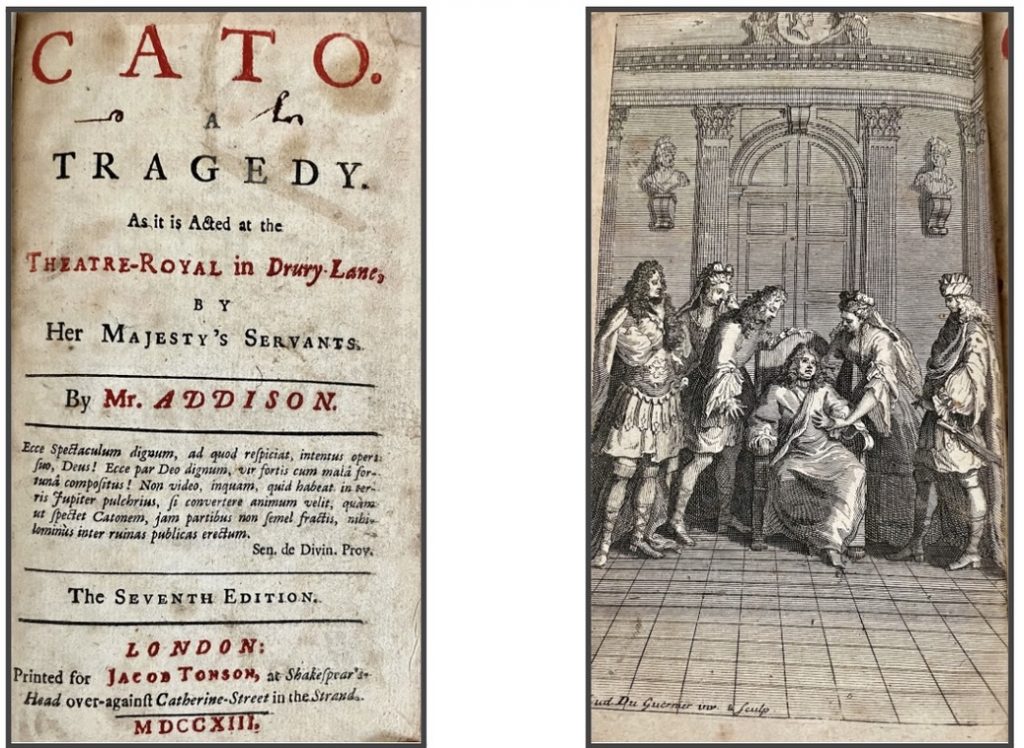

The Founders often looked to ancient Rome for their inspiration. And there was no Roman more admired than Cato. He was a Roman statesman who fiercely defended the Roman Republic against the increasingly unjust and tyrannical acts of Julius Caesar. Joseph Addison wrote a play about Cato in 1713 that was beloved by George Washington. I found an early edition from that same year.

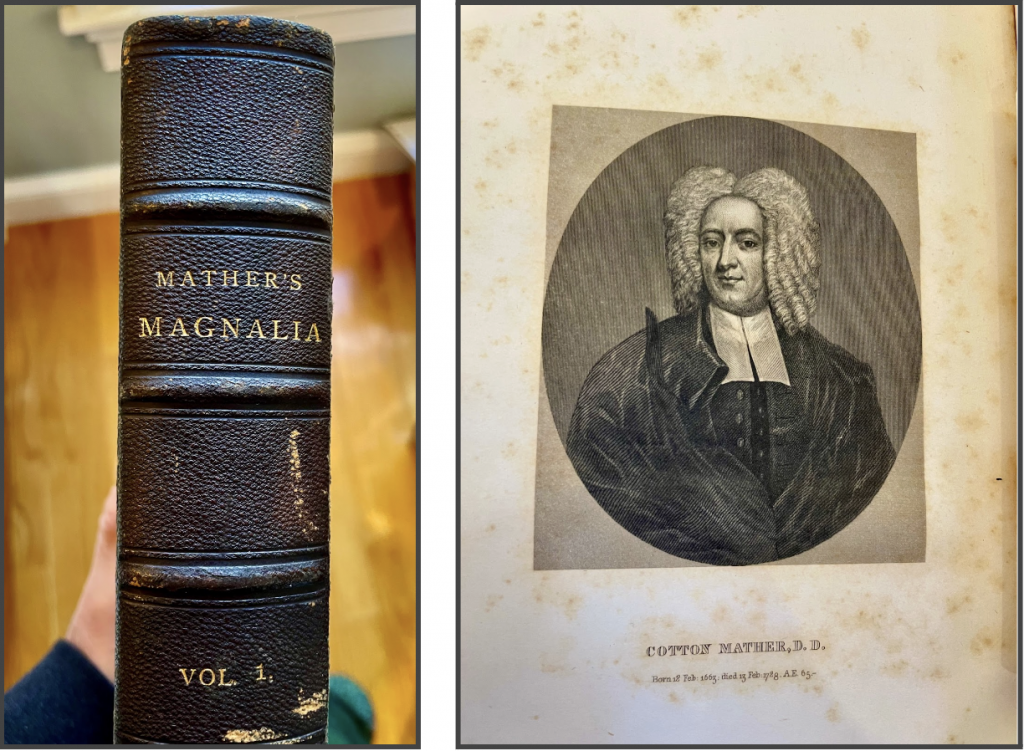

I next delved into the early history of Massachusetts, the place I have spent most of my life. I wanted to own Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana, the most famous history of New England in the 17th Century. Among other interesting topics, it includes details of the Salem Witch trials in 1692, a horrendous failure of the justice system in colonial times in which Mather himself had a direct and complicated role.

A first edition was out of reach for me financially, so I searched for other editions. I then found an association I could not resist. I learned that this book had a great influence on Harriet Beecher Stowe. She recalls in one of her books how happy it made her feel as a child to watch her father acquire a new edition of Magnalia, and how much she loved the stories in it.

The Magnalia I found was the copy owned by the Stowe family. It is the Second American edition from 1853 and has the ownership stamp of Harriet’s husband Calvin, and the signatures of her son Charles and grandson Lyman.

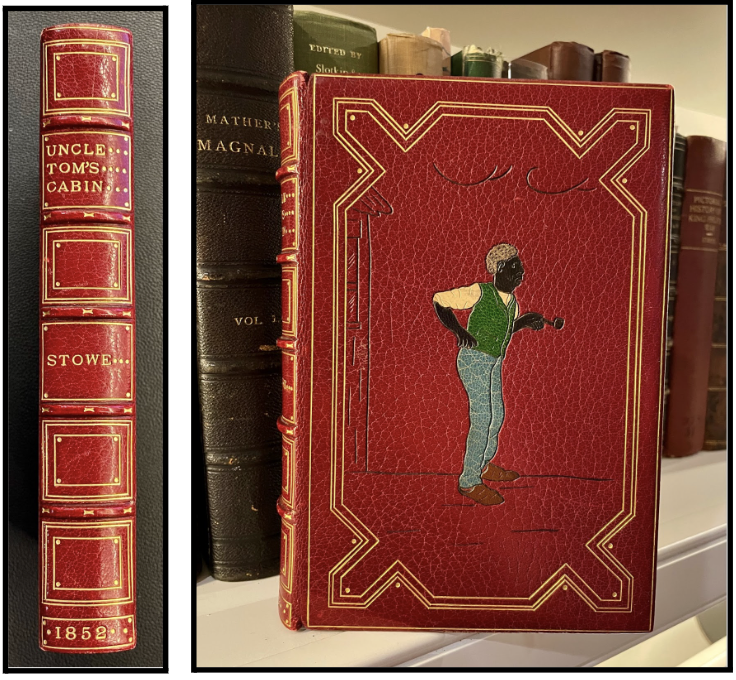

I then had to own Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe’s landmark work that exposed the horrors of slavery. I found a beautifully illustrated English edition with a picture of Uncle Tom on the front board. It was owned by the famous children’s poet Eugene Field. Field’s father, Rosewell Martin Field, was the lawyer who represented Dred Scott, a slave who famously sued for his freedom.

Book collecting became more than I initially thought. A book could tell so many different stories. And the stories I sought were ones that told of the trauma and progress of society, the consequential people who played a part in it, and wherever possible, the connections between them. Whether authors or owners of books, I was intrigued by people who spent their lives in worthy causes to advance society. These people went against the grain of their times to promote the common good. Justice became the animating force of my future collecting.

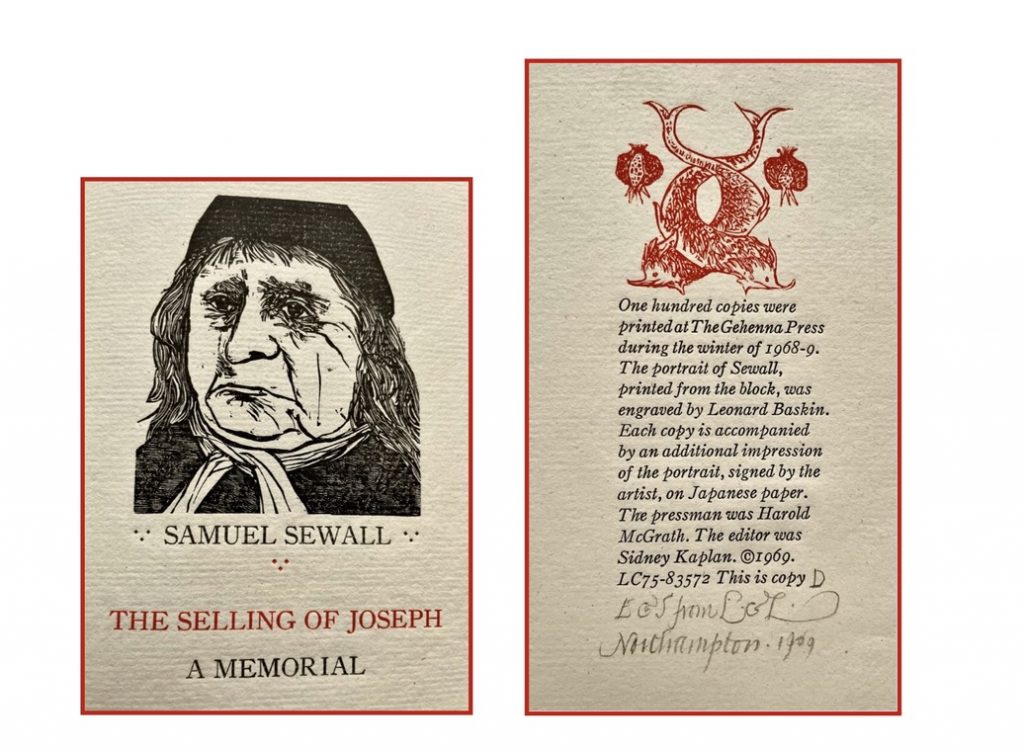

One unlikely advocate for ending slavery was Samuel Sewall. He is best known as one of the judges in the Salem Witch trials. Unlike any other judge on the court, Sewall had deep regrets about the episode and later famously repented in public for the “blame and shame of it.” Thereafter, Sewall devoted his life to doing good, including writing in 1700, The Selling of Joseph, the earliest known tract in America arguing against slavery. I found a beautiful rendition done in 1968 by Leonard Baskin, a famous fine press publisher and illustrator. It was one in a series of tracts seeking to honor critical moments in the struggle for freedom and a more just ordering of society. It was a presentation copy, but the recipient was unknown. I tapped into a new connection I made in the book world to solve the mystery (described in the bibliography).

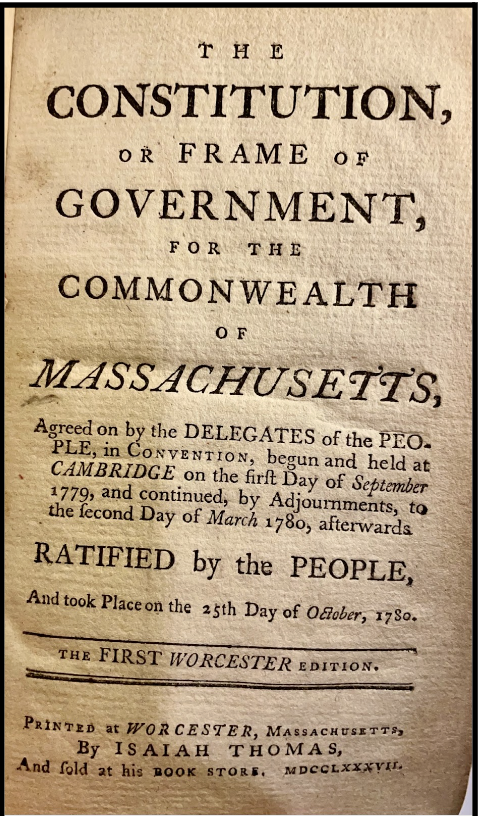

Books that connect to me personally have special meaning. I wanted a copy of the Massachusetts Constitution, written by John Adams in 1780. It was a pioneering work in the protection of individual rights and freedoms. I found a first Worcester edition published in 1787 by Isaiah Thomas (more on him later) that was owned by John Murray. Murray was a Minister in Gloucester who founded Universalism and had to use a clause in this very Constitution to sue his town for religious recognition. My wife and I are beneficiaries, as we are active members of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Sherborn.

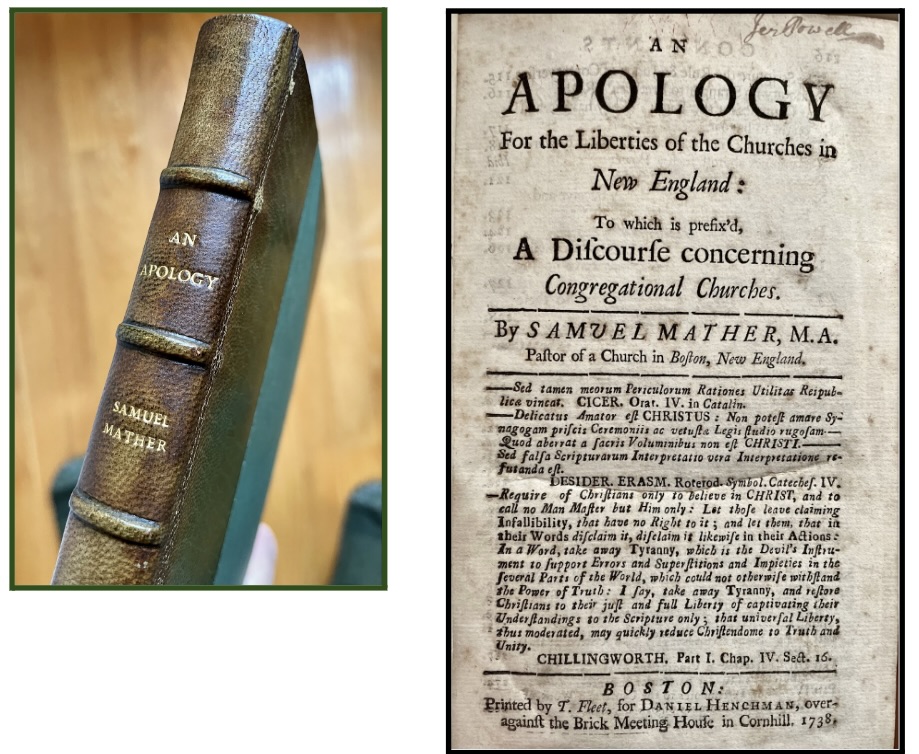

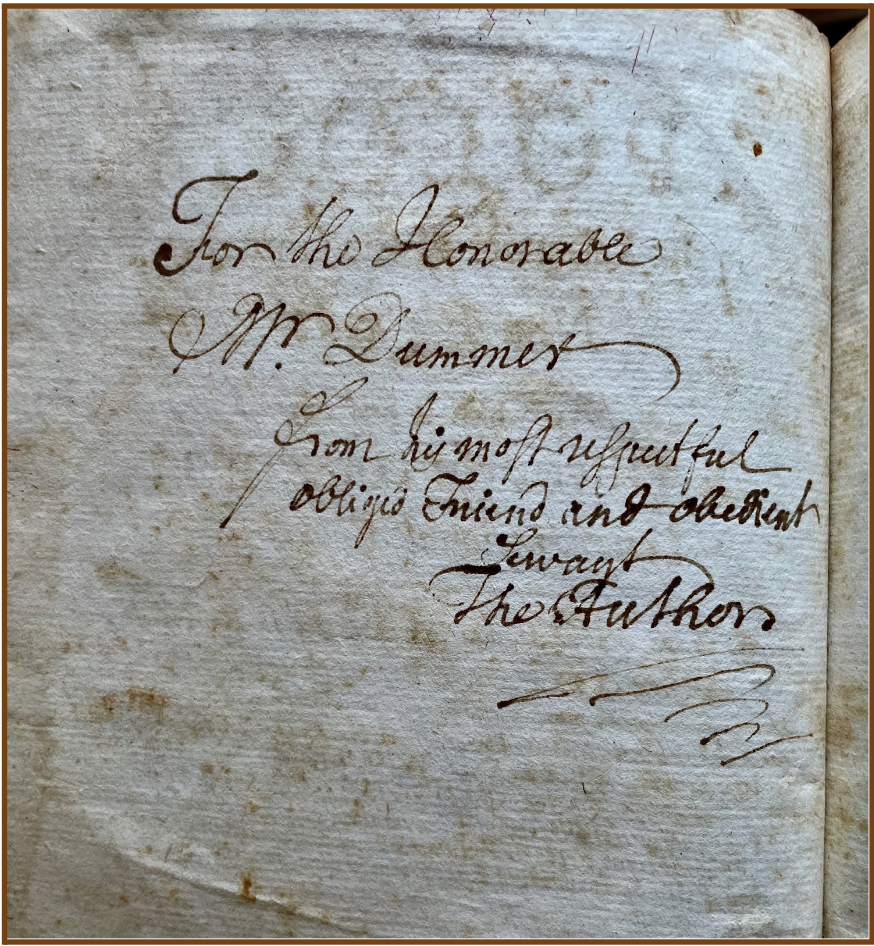

I found a book written by Cotton Mather’s son Samuel in 1738 that argued strenuously for the radical idea of Congregational polity and the rights of congregants to self-governance. It was inscribed by Mather to Lieutenant Governor William Dummer, the founder of the Governor’s Academy in Byfield, the high school from which I would graduate.

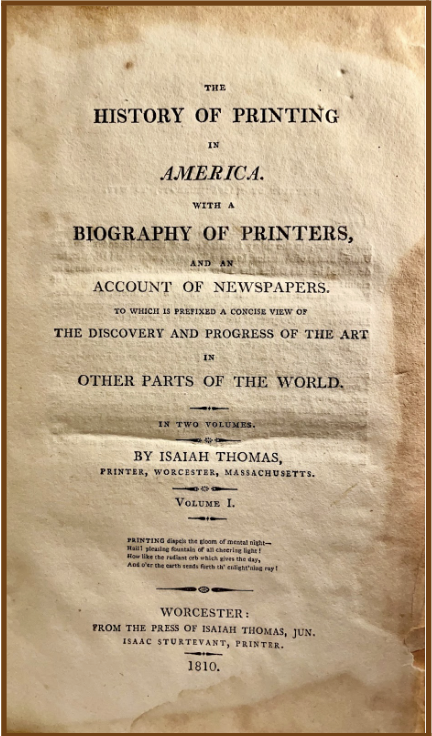

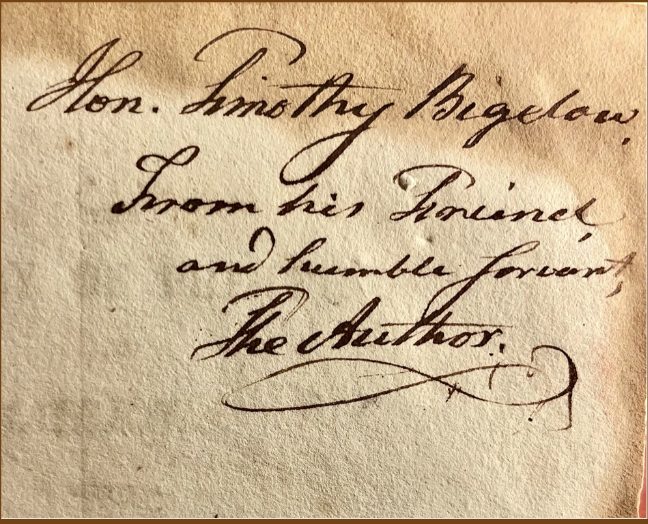

In October of 2021, I was invited into the membership of the American Antiquarian Society. I became fascinated with Isaiah Thomas, the revolutionary patriot and printer who founded the Society in 1812. I bought a first edition of his book, The History of Printing in America. Thomas had inscribed my copy to Timothy Bigelow, a prominent lawyer who helped found the Society with him. Bigelow’s family had a strong connection to Thomas. Bigelow’s father was a revolutionary war hero who had helped Thomas sneak his printing press out of Boston to Worcester a few days before the Battles of Lexington and Concord to avoid British confiscation.

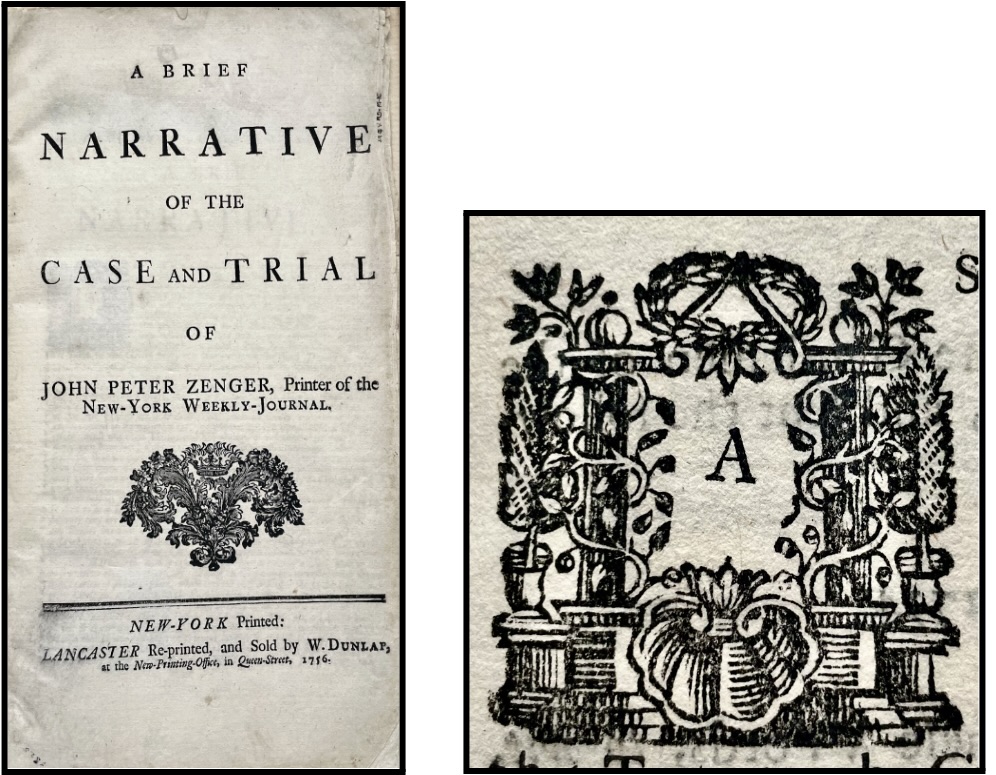

In any story of justice, lawyers are never far behind, and there are many good ones reflected in my collection. Two stand out. Andrew Hamilton defended a little known New York printer named Peter Zenger in 1735 in a masterful performance that became a landmark case on the freedom of the press. James Otis, Jr. represented several merchants in Boston in 1761 when British authorities started arbitrary searches of ships for smuggled goods. His advocacy was so brilliant that John Adams called it the first significant act of the revolution.

One thing I have learned in my quest is that there are many important stories that remain untold. This is especially true for groups underrepresented in our history, including Native Americans, African Americans and women. In my future collecting, I will seek out more of these untold stories, and do my best to share them with the world.

***

I am now forty-six years removed from my eighth grade performance. I have traveled far, but could the best be yet to come?

In his book From Strength to Strength, Arthur Brooks discusses two intelligence curves. The first – fluid intelligence – involves reasoning and solving complex problems. It is the intelligence we use to build a career. But it starts to decline in our 40’s.

The second curve – crystalized intelligence – starts later in life and involves knowledge gained through experience. It gives us wisdom and perspective.

Many cling to their fluid intelligence long after its decline, desperately trying to function at the level of their old selves. The secret to a satisfying second half of life, Brooks says, is to find an avocation that allows you to “jump the curve,” so you can tap into your crystallized intelligence, which improves with age.

I turn 61 in September. I started my collecting journey when I was 57. I am unquestionably a “late blooming” bibliophile, but I may have found my way to jump the curve.

Doug Brown’s thirty-five year professional career has taken him through the law, government and health care. He recently retired as an executive at UMass Memorial Health in Worcester, Massachusetts. Doug was elected into the membership of the American Antiquarian Society in 2021 and currently serves on its governing council. He is a member of the Grolier Club, the Caxton Club and the Ticknor Society. Doug will describe his “wild adventure” into the world of provenance and association in an upcoming essay in the May/June edition of The Caxton Club’s Caxtonian.

Catalogue

The following catalogue is organized chronologically, not by acquisition date as in the essay, in order to give the reader a better sense of how these events unfolded in history. The date of first publication is used for the ordering, even if the book referenced is of a later edition. Ten of the following twenty items were not referenced in the essay, but comprise an important part of my collection. These additional items were selected based on the extent to which they lift up my theme of justice.

The Eighteenth Century represents the period of my greatest focus and interest, but all told the following works represent 340 years of individuals seeking justice, advancing society and sharing their humanity with each other.

Each item contains a descriptive essay of no more than 250 words (exclusive of the bibliographical descriptions) in accordance with the guidelines. At the end of the bibliography, I include a selected list of sources and other references, for further exploration of the people, books and topics covered herein.

Finally, one of the great joys of my collecting has been the wonderful book people I have met along the way. I am particularly grateful for the kindness shown to me by the following individuals, all of whom patiently helped to guide me on my path: Donald “Rusty” Mott of Howard S. Mott, Inc.; Nick Aretakis of the William Reese Company; Clarence Wolf of MacManus Rare Books; Heather O’Donnell of Honey and Wax Books; Lisa Unger Baskin; and James Glickman.

1677

(1) GOOKIN, Daniel. An Historical Account of the Doings and Sufferings of the Christian Indians in New England, In the Years 1675, 1676, 1677. Impartially drawn by one well acquainted with that affair, and presented unto the Right Honourable the Corporation residing in London, appointed by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty for promoting the Gospel among the Indians in America. Cambridge: Included in Archaelogia Americana, the Transactions of the American Antiquarian Society, Volume II (pages 423-534), 1836. Brown paper boards. Octavo. Water stains on cover, significant foxing throughout. Good condition.

Daniel Gookin was a high ranking government official in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and supervised the so-called Praying Indians; Native Americans who converted to the English ways of life and practiced Christianity. Gookin and John Eliot helped these Native Americans establish several settlements across the state, the most famous of which was in Natick.

In 1675, growing tensions between Native Americans and English settlers erupted into King Philip’s War. The war had devastating consequences. Thousands of lives were lost and 12 towns were completely destroyed. The Praying Indians were caught in the middle, and they were horribly treated by both sides. King Philip’s men saw them as traitors (they supported the English) and the English mistrusted them due to the color of their skin. Hundreds were rounded up and shipped to Deer Island in Boston Harbor, where many would die of starvation and exposure to the bitter cold.

Throughout it all, Gookin fiercely defended and actively helped these Praying Indians. His life was repeatedly threatened and he was voted out of office. Yet he never gave up. He wrote this manuscript in 1677 after the war to document their awful plight. He sent it to his sponsors in England for publication, but they deemed it too radical to do so. There it sat for more than 150 years until it was miraculously discovered and made its way to the American Antiquarian Society, where it was first published in 1836. Without Gookin, we would never know the full story.

1701

(2) SEWALL, Samuel. The Selling of Joseph – A Memorial. [Emma and Sidney Kaplan]. Northampton, MA: The Gehenna Press, 1968. Quarter tan morocco with marbled boards, bound by Arno Werner, Pittsfield, MA. 8 ½ x 5 ¾. 65 pages. Fine Condition. With a wood engraving of Sewall by Leonard Baskin and an essay by editor Sidney Kaplan. Accompanied by an additional impression of the portrait, signed by Baskin, on Japanese paper. Limited edition of 100. This is copy D, below colophon written in pencil is the following inscription: “E & S from L & L Northampton. 1969.

Gookin and Samuel Sewall were contemporaries, and seemingly shared a yearning to help promote a more just society. In this work, Sewall used the bible to support his arguments that slavery was unjustified and sinful. ”It is most certain that all Men, as they are the Sons of Adam … have equal Right unto Liberty, and all other outward comforts of life.”

I wanted to own this work, but a first edition was unavailable (there is only one known existing copy, and it is held by the Massachusetts Historical Society). I was thrilled to find this beautiful rendition designed by Leonard Baskin and edited by Sidney Kaplan of the Gehenna Press. Baskin said of the work that it “is expressive of Sidney Kaplan’s editorial role in providing to the press generally inaccessible texts of importance.”

I knew that the “L & L” inscription was from Leonard and his wife Lisa Unger Baskin (herself a notable collector), but I did not know the identity of the “E & S” to whom it was inscribed. The mystery was solved when I reached out to Lisa, having recently presented on a panel with her. She responded that she was “quite certain that the inscription was for Emma & Sidney Kaplan” and noted that “the entire series, the Gehenna Tracts, was published because of Sidney Kaplan.” It turns out that the Baskins and Kaplans were close friends. It was such a joy to learn of this amazing connection between these consequential individuals.

1701

(3) SHERBURNE, Sir Edward (translator). The Tragedies of L. Annaeus Seneca the Philosopher. Medea, Phaedra and Hippolytus, and Troades, or the Royal Captives. Translated into English Verse with Annotations. To which is Prefixed the Life and Death of Seneca the Philosopher; with a Vindication of the said Tragedies to Him, as their Proper Author. [Abednego Seller]. London: Printed for S. Smith and B. Walford, 1701. Modern three-quarter brown morocco over brown paper boards, raised bands, spine and boards ruled in gilt, red morocco spine label lettered in gilt, all edges stained red. Octavo. Fine condition. Engraved frontispiece portrait of Seneca and five engraved plates throughout. First edition, first issue. SIGNED PRESENTATION INSCRIPTION by Edward Sherburne to Abednego Seller as follows: “For the Reverend and Learned Mr. Ab: Seller / From his most obliged, and (tho unfortunate) most Grateful, Affectionate, humble, Servant. / Edw. Sherburne.”

Seneca has always fascinated me. Much like Samuel Sewall, he was an enigma. He left us beautiful works of Stoic philosophy articulating how to live a life of virtue, yet served as a close adviser to Nero, one of the most treacherous Emperors of the Roman Empire. So why did he write tragedies? Perhaps it was to connect more deeply to the tragic parts of his own life. And that may also be true for this translator, Edward Sherburne.

Sherburne was caught on the wrong side of the English civil war in the 17th Century. Because he was a loyalist and Roman Catholic, he was stripped of his post as Clerk of the Ordnance and put in prison. His entire estate was confiscated, and his substantial library was destroyed. He was protected later in life when the monarchy was restored, but as a Roman Catholic he refused to take the oath of William and Mary and was deprived of his livelihood and fell into “unfortunate” times. The inscription is to a friend and clergyman, Abednego Seller, who also had to forfeit his position under the Glorious Revolution, and whose library was also lost to a fire.

One senses a deep connection between these two men over shared tragedy, injustice, and the love and loss of books. The inscription (following page) exudes humanity, and the fact that the book is about tragedies by another tragic figure makes it all the more meaningful to me (and presumably to them).

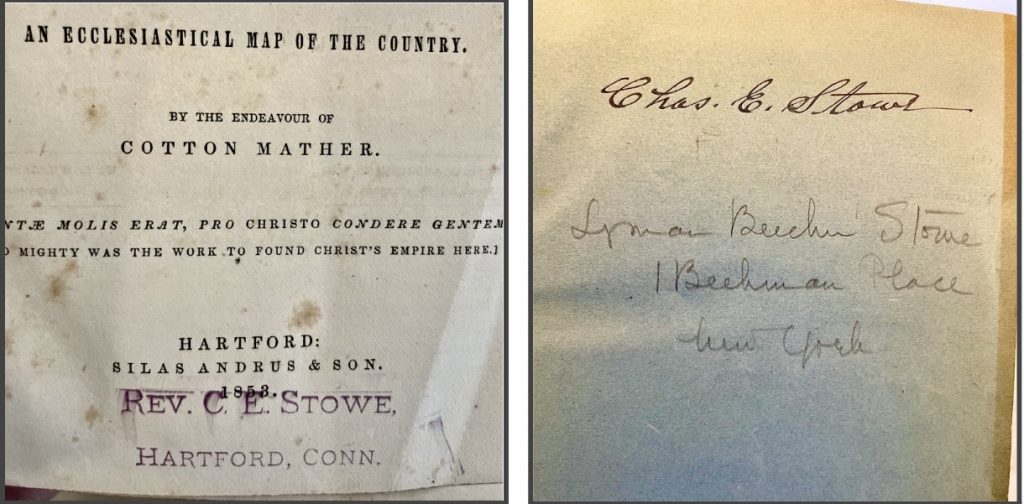

1702

(4) MATHER, Cotton. Magnalia Christi Americana; Or, The Ecclesiastical History of New England, from its first Planting in the year 1620, … to 1698 … In Seven Books, Two Volumes. [Harriet Beecher Stowe]. Hartford: Silas Andrus and Son, 1853. Bound in three quarters leather, gilt titles to the spine. Grey cloth boards, blue endpapers. Octavo. Scattered light foxing, very good condition; occasional pencil underlines and annotations, presumably by a member of the Stowe family (one such annotation on p. 70 of vol. 1 appears to be in Calvin’s hand based on comparison with one of his letters in the Beecher-Stowe family papers at Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library). Frontispiece of Mather to volume one. Second American Edition. SIGNED: ownership stamp of Harriet’s husband Calvin E. Stowe on title page of each volume; signatures of her son Charles E. Stowe and her Grandson Lyman Beecher Stowe on front endpaper of each volume.

This captivating book includes the religious history of Massachusetts, details on the Salem Witch trials, biographies of well known leaders, and the story on the founding of Harvard College. Howes describes the work as the “most famous 18th Century American book.” And this copy was owned by one of the most famous 19th Century American families. In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book, Poganuk People (1878), considered her autobiography, she wrote how she marveled as a child at watching her father in his study surrounded by all those awe-inspiring books.

“But there was one of her father’s books which proved a mine of wealth to her. It was a happy hour when he brought home and set up in his book-case Cotton Mather’s Magnalia in a new edition of two volumes. What wonderful stories these? And stories, too, about her own country, stories that made her feel that the very ground she trod on was consecrated by some special dealing of God’s providence.”

This work greatly influenced Harriet throughout her life. This copy was not likely the one referenced above (she was over 40 in 1853 when this edition was published), but it was undoubtedly a copy greatly cherished by her and her family, as it was passed down to her son Charles and her grandson Lyman, both of whom signed the front endpaper.

I am intrigued by the Mather-Stowe connection and wonder whether something in Magnalia may have influenced Harriet’s views on slavery and her writing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

1713

(5) ADDISON, Joseph, Cato A Tragedy, As it is Acted at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane, By Her Majesty’s Servants. London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, at Shakespear’s-Head over-against Catherine-Street in the Strand, 1713. Modern blue binding, gilt lettering on spine. Title page black and red. Includes annotations of the play’s release by an 18th Century owner. Minor spotting and foxing throughout. Engraved frontispiece illustration of scene from play. Very good condition. The Seventh Edition.

The Stoic concept of Justice was a bit different from how we think of it today. It involved a moral duty that one owed to others, and to society at large. It was akin to virtue. And to our Founders, there was nothing more important than virtue. It essentially meant to put the interests of the State ahead of your own, and it was fundamental to public life.

Cato was the model. A Roman Senator during the waning days of the Republic, he was known for his honesty, integrity and commitment to principle. He opposed Julius Caesar at every turn and, in the end, when he was cornered by Caesar’s troops, he chose heroically to take his own life instead of pleading for mercy.

Joseph Addison dramatized the story in this tragedy published in 1713. It was an instant success and was beloved by the revolutionary generation. George Washington had his troops act it out at Valley Forge to lift their spirits. Patrick Henry used the play as his source for his famous statement: “Give me liberty or give me death.”

I love this little volume published almost twenty years before George Washington was born. When I ponder our politics today, I worry that we have turned virtue on its head; any notion of public responsibility seems frequently to give way to private interests. I wonder how much better off society would be if we still prized virtue as much as our ancestors did.

1731

(6) WATTS, Isaac, The Strength and Weakness of Human Reason: or, the Important Question about the Sufficiency of Reason to Conduct Mankind to Religion and Future Happiness, Argued Between an Inquiring Deist and a Christian Divine: and the Debate Compris’d and Determin’d to the Satisfaction of Both. By an Impartial Moderator. [James Otis, Jr.]. London: C. Rivington, 1737.Contemporary speckled calf, covers ruled in gilt. 12mo. Bindings heavily worn, front cover detached, lacks front endpapers. Title in red and black. Second Edition. Signature and partial bookplate of James Otis, Jr., signatures of Mary Otis (daughter) and Polly Otis.

In 1760, the British government authorized customs agents to use “writs of assistance” to arbitrarily inspect ships or buildings in America they suspected might hold smuggled goods. At the time, Otis was one of the most brilliant lawyers in Massachusetts. He was so outraged by this policy that he gave up his role as Advocate General and switched sides to defend several merchants who were fighting the orders.

At the trial in 1761, Otis was electrifying. He called the writs, “the worst instrument of arbitrary power … that ever was found in an English law-book ….” Despite his powerful oratory, he lost the case. But he didn’t lose the audience, which included a young John Adams. Adams was so impressed by Otis that he later said, [t]hen and there the Child Independence was born.”

Sadly, Otis would suffer from severe mental illness later in life, apparently exacerbated by a bar room fight. He withdrew from public view and inexplicably destroyed most of his papers. As a result, there are very few books from his library on the market. I was thrilled to acquire this one.

Isaac Watts is mostly known for his hymns, but his educational works were used as text books for instructing college students on logic and reason. Otis may have acquired this when he entered Harvard in 1739 at age 14. Perhaps this book helped prepare him for developing his arguments in the case that would later make him famous.

1736

(7) ZENGER, John Peter, A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, Printer of the New-York Weekly-Journal. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: W. Dunlop, 1756. Late 19th Century blue morocco binding, spine gilt, raised bands, with 18th Century plain blue wrapper before title page. Folio. Text shaved unevenly along foredge, affecting words on text on eight pages. Very good. Third American Edition.

Andrew Hamilton was a prominent Philadelphia lawyer who represented Peter Zenger, a printer of the New York Weekly Journal. The paper was highly critical of William Cosby, the colonial Governor of New York, who had a tendency toward arbitrary actions. To exact revenge, Cosby accused Zenger of seditious libel – the intentional publication of any written blame against a public official. At the time, unlike today, truth was not a defense to such a claim.

At trial, Hamilton employed a bold strategy. He admitted that Zenger printed and published the matters at issue, freeing the prosecutor from having to prove his case. With this admission, the judge could have immediately directed a verdict against Zenger. But Hamilton calculated that, in such a high profile trial, the judge would not want to appear biased by prematurely ending the trial without giving Zenger a fair hearing. Hamilton’s bet paid off. He was allowed to proceed, and argued eloquently that the jury should basically ignore an unjust law. By the time the judge gave instructions, it was too late. The jury had already taken justice into its own hands. Not guilty! Hamilton was immediately hailed as a hero, and the trial would become the most celebrated case in the colonies for protecting freedom of speech.

This copy of the trial transcript was a later edition from 1756 by printer William Dunlap. My guess is that it was printed to honor James Alexander, another prominent lawyer in the case who died that same year.

1738

(8) MATHER, Samuel. Apology. [William Dummer]. Boston: T. Fleet for Daniel Henchman, 1738. Modern three-quarter green morocco gilt, raised bands, marbled endpapers. Octavo. Scattered light foxing, dampstaining. Spine toned to brown. Very good condition. First Edition. SIGNED PRESENTATION INSCRIPTION opposite the title page as follows: “For the Honorable Mr. Dummer from his most respectful, obliged Friend and obedient Servant, The Author.”

Cotton Mather lived during a time of superstition and Witches. But thirty six years after publication of Magnalia, Cotton’s son Samuel published this work, which is reflective of a very different time. Society was advancing and principles of the enlightenment had started to take root, including, as we have seen, liberty, reason, and the freedom of individuals to govern themselves. One area this revealed itself was in affairs of religion, and in the Apology, Samuel Mather (Pastor of the Second Church of Boston) zealously defended the right of congregational churches to govern themselves, including choosing their officers and ordaining their ministers. This concept of congregational polity would later become the fertile soil of American Democracy.

I enjoy seeing this societal transformation take place through the writings of one famous New England Puritan clergyman and his lesser known, but more progressive son. But this piece connected with me on two additional levels. First, I am the Moderator of my Church and run its Annual Meetings. Church governance is near and dear to my heart and seeing it defended so passionately in 1738 is inspiring. But the association was what really grabbed me. William Dummer founded the Governor’s Academy in Byfield in 1763. I graduated from that high school 218 years later. Dummer appears to have been friendly with Samuel Mather and subscribed to his 1729 biography of Cotton.

1749

(9) MONTESQUIEU, Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède. The Spirit of the Laws.

Translated from the French … With corrections and additions communicated by the author. London: Printed for J. Nourse, and P. Vaillant, in the Strand, 1750. Contemporary three-quarter calf over marbled boards, spines with gilt-lettered morocco label and raised boards. Octavo. Two volumes. Bindings minor rubbing; joints repaired. Text with some minor browning; small restoration to title pages not affecting text. Very good condition. First English Edition.

Eleven years after Samuel Mather addressed governance issues for religious communities, in another part of the world Montesquieu took on the topic for society at large. It was an earth shattering work that still guides and inspires judges and politicians across the Globe.

Montesquieu had broad intellectual range. He was a judge, scientist, novelist, historian and traveler. He spent twenty years preparing this work, which applied a scientific and historical approach to studying government and understanding the factors at play in human attempts to govern themselves.

Although this book covers many topics, the most famous part for Americans is its discussion of the need for a separation of powers in government in order to have effective checks and balances. This work was hugely influential on our Founding Fathers and formed the basis for our own separation of powers in our Constitution. As I struggled to make sense of what happened to our government on January 6, 2021, this book gave me hope. It was like a calm whisper saying: “Your government was built on sound principles. This, too, shall pass.”

1764

(10) BECCARIA, Cesare Bonesana di, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, Translated from the Italian; with a Commentary attributed to Mons. De Voltaire, Translated from the French. London: Printed for F. Newbery, at the Corner of St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1775. Contemporary calf, spine ruled in gilt, red and black spine label lettered and decorated in gilt. 8 ½ x 5 ⅜. Binding slightly worn. Occasional marginalia in pencil. Tear on title page not affecting text. Very Good Condition. The Fourth Edition.

Inspired by Montesquieu in France, Beccaria in Italy wanted to dig deeper on one important aspect of government: crimes and punishment. Prior to this time, punishment was rather arbitrary, and it was not uncommon for judges to impose brutal torture and other severely cruel measures. Beccaria sought to change that. In order for punishment to be just, “it should be public, speedy, necessary, the minimum possible in the given circumstances, proportionate to the crime, and determined by the law.” He argued passionately for a sense of proportionality; punishments should fit the crime. The more proportionality in the criminal justice system, according to Beccaria, the “higher level of civilization and humanity” in a country. He was among the first writers to argue against the death penalty, finding that it has a brutalizing effect on society, “because of the example of savagery it gives to men.”

Like Montesquieu, Beccaria had a huge influence on our Founders. Jefferson reportedly copied whole pages into his commonplace book. Adams quoted Beccaria at the beginning of his argument in defense of the British soldiers charged in the Boston Massacre. This work greatly influenced the development of the criminal laws in our country and around the world.

My copy is the Fourth Edition, published 11 years after the First Edition. I was attracted by the contemporary binding and decorative spine, and the fact it includes a commentary from Voltaire.

1773

(11) WHEATLEY, Phillis. “On Recollection,” The Gentleman’s Magazine. London: Printed for D. Henry at St. John’s Gate, September, 1773, p. 456. Lacks covers.

Phillis Wheatley was the first African American author to publish a book of poetry. And she did so while enslaved. Phillis was captured in West Africa as an eight-year-old and sent to Boston, where she was purchased by John Wheatley and his wife Susanna. She was educated and taught to read and write. Her brilliance immediately revealed itself. She learned Greek and Latin and published her first poem in 1767, at age 14.

Phillis traveled with an escort to London in May of 1773 to find a book publisher. She stayed until September, the same month this article (and her first book of poems) was published. She returned to Boston that month to take care of Susanna Wheatley who had become ill. Some believe she returned only after being assured of her freedom, which she gained shortly thereafter.

This article was most interesting to me because of the biographical footnote. At the time, England had very different views of slavery than America, and Phillis’s enslaved status drew significant attention and scorn, as is evident in portions of the footnote:

“Youth, innocence, and piety, united with genius, have not yet been able to restore her to the condition and character with which she was invested by the Great Author of her being. So powerful is custom in rendering the heart insensible to the rights of nature, and the claims of excellence!”

I wonder whether the warm reception she received in London may have helped to influence her ultimate path to freedom.

1780

(12) ADAMS, John. The Constitution or Frame of Government for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. [William Hambley] Worcester, Massachusetts: Isaiah Thomas, 1787. Contemporary calf, rubbed and rebacked. 12mo. Very Good. The First Worcester Edition. SIGNED PRESENTATION INSCRIPTION on the second front free endpaper, as follows: “For Mr. William Hambley from his obliged and gratefully affectionate friend John Murray. Gloucester Oct. 10 1791.”

The Massachusetts Constitution is the world’s oldest functioning written constitution. It served as a model for the United States Constitution and for the constitutions of many countries around the world. It is the first to include a declaration of rights and provisions for the separation of powers. But what I especially like about this document (which will appeal to most book people) is that it has a separate section for “the encouragement of literature,” recognizing quite clearly that “wisdom, and knowledge, as well as virtue … [are] necessary for the preservation of [] rights and liberties; and [] these depend on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education …”

Education may be the most important ingredient in the advancement of society, and I admire that this was recognized and supported in the Commonwealth’s groundbreaking constitution.

This copy appealed to me both because it was the first Worcester edition printed by Isaiah Thomas, and because it was once owned by John Murray, the founder of Universalism. I am co-leading a Coming of Age Program this year for youth at my Unitarian Universalist church and I shared this book at one of our classes on the history of our faith. I’m not sure these 8th graders appreciated it quite as much as I do, but given my own 8th grade attention span, I have no standing to complain.

1798

(13) WASHINGTON, Bushrod. Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of Virginia [Dedication Copy]. Richmond, Virginia: Thomas Nicolson, 1798 and 1799. Contemporary sheep, not uniform. Two volumes. Octavo. Volumes worn; first volume joints cracked; second volume upper board and flyleaf detached. Intermittent browning, some damp staining. First Edition. Vol. 1 is Dedication Copy. Provenance of Edmund Pendleton (partially effaced inscription on flyleaf and numerous marginal comments).

[With:] Autograph note signed by Thomas Jefferson (“Th:J”) to James Leitch, [Monticello], 22 March 1822: “a bar of tire iron” and “a sack of salt.”

There are many stories behind this book. But it starts with Bill Reese. Bill was a renowned collector of Americana who died prematurely in 2018. I never met Bill, but I benefited greatly from his work. When I learned that Christie’s would be auctioning off his private collection, I knew I had to participate. It was my first auction (most of my purchases have been done online or through a handful of reputable book sellers I have come to know), so I didn’t know what to expect. Most items were out of my reach. I would have settled for anything owned by Bill, but I was thrilled to get this item that fits so well into my collection.

Bushrod Washington was a Virginia jurist and the nephew of George Washington. He would later inherit Mount Vernon. Since Virginia was mature in its jurisprudence, its cases were helpful to the relatively new Supreme Court of the United States (on which Bushrod would later serve).

This was a collection of Virginia appellate cases and contains a dedication to Edmund Pendleton, a renowned Virginia judge who was a mentor to Bushrod and John Marshall. Volume 1 was Pendleton’s own copy and contains some of his annotations.

Bushrod and Pendleton mingled with other famous Virginians. That likely explains the other pleasant surprise: a tipped in note from Thomas Jefferson ordering “a bar of tire iron [and] a sack of salt” from a merchant friend who would later help him found the University of Virginia.

(14) THOMAS, Isaiah. Bookplate [William Augustus “Whizzer” Wheeler; Meg Wheeler] Engraved by Paul Revere. 1798 (approx.). Accompanied by Letter dated 8 April 1982 from American Antiquarian Society Director Marcus McCorison to Mr. and Mrs. William Wheeler enclosing bookplate as a gift. Very good condition.

Isaiah Thomas lacked formal education, but had a keen intellect and strong drive. He began publishing The Massachusetts Spy in 1771, and it became one of the most influential newspapers in Colonial America for circulating revolutionary opinion. British authorities repeatedly tried to shut it down, and Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson referred Thomas to the Attorney General for sedition, but the Grand Jury refused to indict. Like Peter Zenger before him, Thomas was dogged in his pursuit of a free press to advance the rights of citizens against tyranny.

Once I learned that Thomas’s bookplate was designed by Paul Revere, I wanted to own one. The provenance on this one appealed to me because of my shared interests with its prior owner. William “Whizzer” Wheeler was born in Worcester, Massachusetts and became an early pioneer of American manufacturing processes. When he retired, “he indulged his lifelong love of history.” He gathered and curated “an impressive collection of autographs and historical documents [and] was proud to have been elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.”

Wheeler apparently got to know Marcus A. McCorison, former Director at the AAS and made some donations to the institution. In return, as a gift, McCorison writes that he “was able to find a bookplate of Isaiah Thomas’s, engraved by Paul Revere and take pleasure in forwarding it to you.”

1810

(15) THOMAS, Isaiah. History of Printing in America. With a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers. To which is Prefixed a Concise View of the Discovery and Progress of the Art in Other Parts of the World. [Timothy Bigelow]. Worcester, Massachusetts: Isaiah Thomas, 1810. Modern, antique style binding. Ruled in gilt, red spine label lettered in gilt. 8 ½ x 5 ¼. Some damp staining to select pages, not affecting text. First Edition. SIGNED PRESENTATION INSCRIPTION: “Hon. Timothy Bigelow | From his Friend and humble Servant | The Author.”

Timothy Bigelow served as an apprentice in Isaiah Thomas’s printing office. He went on to become one of the most prominent lawyers in the Commonwealth, and later served as Speaker of the Massachusetts House. Bigelow and Thomas shared a “passion for books and a strong love of literature,” and they would later join together to found the American Antiquarian Society.

Thomas tapped into the many contacts he had in the field to collect information for this book, which remains one of the most authoritative sources on the history of printing in America. But what would he do with all the books, pamphlets, newspapers and other materials he collected in his research? Perhaps embodying the literature clause of the young Massachusetts Constitution (see item (12)), Thomas came up with the idea of creating a society to “enlarge the sphere of human knowledge … and to improve and instruct posterity.” The AAS was thus born and still thrives today. It contains the world’s largest collection of books, pamphlets, newspapers and other materials of early America.

In a memoir of Isaiah Thomas for the AAS, his friend Samuel Burnside described Thomas’s passion for collecting with words that resonate deeply with me: “To collect and preserve whatever could tend to illustrate the genius and exact condition of society at different epochs in its advancement from one state of improvement to another, was ever a favorite employment of Mr. Thomas, and formed a prominent habit of his life.”

1820

(16) IRVING, Washington. “Philip of Pokanoket,” Ladies’ Literary Cabinet. New York: Samuel Huestis, Publisher, August 26, 1820. Volume II, No. 16. Loose and unbound. Some tearing at edges. Good condition.

Winston Churchill said that history is written by the victors. Nowhere is that more apparent than with King Philip’s War. While Gookin’s manuscript sat in England collecting dust (see item 1), the other contemporary histories were written by white English men with biased perspectives. Those histories were then baked into our culture, along with their biases. King Philip (Metacom) and his followers were depicted unfairly as evil and savage barbarians, and this view carried over to all Native Americans.

The narrative started to change around the time of the War of 1812. One of the first authors to explore this was Washington Irving. He had the courage to re-examine some of the underlying assumptions, which led to a more accurate and balanced perspective on the conflict. In this piece, he presents Metacom in a far more positive and sympathetic light:

“With heroic qualities and bold achievements, that would have graced a civilized warrior, and rendered him the theme of the poet and the historian, he lived a wanderer and a fugitive in his native land, and went down, like a foundering bark, amid darkness and tempest – without an eye to weep his fall, or a friendly hand to record his struggle.”

There is a Nigerian proverb that states: “Don’t let the lion tell the giraffe’s story.” Unfortunately, in the history of America, most of the stories have been told by the lion. We need to seek out more giraffe stories. In my collecting, I aspire to do so.

1852

(17) STOWE, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. [Eugene Field]. London: John Cassell, Ludgate Hill, 1852. Red crushed morocco Kelliegram-style binding, depicting Uncle Tom holding a pipe on front board, gilt-decorated raised spine bands, compartments ruled in gilt, inner gilt dentelles, marbled endpapers. 7 ½ x 5. Fine condition. With illustrations by George Cruikshank. First English Edition. With bookplate of children’s author and bibliophile Eugene Field on front pastedown. On verso of rear endpaper is following INSCRIPTION: “This book came from the library of my father Eugene Field. Eugene Field II, Sept. 1, 1924.”

This is one of the most beautiful books I own. The binding is gorgeous and gilt abounds. The illustrations are exquisite. And yet, the most interesting thing to me remains the provenance. Eugene Field is well known (journalist, humorist, children’s poet and bibliophile), but his father interests me more. I learned that he was the lawyer who filed the initial lawsuit on behalf of Dred Scott in federal district court in St. Louis. Perhaps to honor his father’s passion for justice, Eugene Field bought the nicest copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin he could find.

But the plot thickens. In my research, I learned that Eugene’s son was a known forger. When his father died in 1895, he sold all of his many books. He discovered that if he wrote in the names of other famous people, he could increase the value. He would then sign the end papers, as he did here, to make it seem more authentic.

So was this one of the forgeries? Unlikely. The purpose of adding famous names was because his father’s name was declining in value. So why would he buy an expensive book and add only his father’s name? Moreover, it makes sense why his father would have owned a beautiful copy of this book. But who really knows? Collecting for provenance and association is not for the faint of heart. Mistakes can happen and I have become OK with that. It is just one more opportunity for learning (and another story).

1965

(18) JOHNSON, Lyndon Baines. The President Speaks: A More Beautiful America. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1965. Original green cloth, in the original pictorial slipcase. Quarto. Near fine condition. Slipcase has a small water stain but is otherwise in near fine condition. Illustrated with photographs by Ansel Adams. Collection of speeches by President Johnson on protecting the environment. Inserted into a pocket affixed to the verso of the rear panel is: ‘A Message on National Beauty by Lyndon Baines Johnson.’. SIGNED PRESENTATION INSCRIPTION, by the author on the title page: “To Jean and Bill Baxter from their friend Lyndon B. Johnson.”

Bill Baxter was the rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Washington, DC. He came to the church in 1954 seeking to revitalize the Congregation. He introduced dance and drama into the liturgy and opened the church to everyone, including “bored Christians, skeptics, agnostics and nonbelievers.”

On November 23, 1963, Baxter received a call that would permanently embed him into our national history. It was from the Secret Service. President Johnson, sworn in as President the day before upon the assassination of John F. Kennedy, was to attend his first service as President at Baxter’s Church.

Baxter had twenty-four hours to completely rewrite his sermon. It would be broadcast to the nation and preserved in the National Archives. But what would he say? He acknowledged the national moment and the frailty of the human condition and its institutions. And he urged against complacency. “[We] are responsible every day to care for [these institutions], to be concerned about them, to sustain them, to uphold them with our votes, our study, our honest understanding of what strengthens us and keeps us going.”

Interestingly, Johnson would hit a similar theme in this book, noting that environmental protection “will require the concern and action of individual citizens, alert to danger, determined to improve the quality of their surroundings … demanding and building beauty for themselves and their children.”

1970

(19) WOOLMAN, John. Dream of the Fox and the Cat. Northampton. Gehenna Press, 1970. Broadside, with a woodcut drawn by Leonard Baskin and cut by John Keith. 26 ¼ X 23 ¾. 1 sheet, untrimmed. Very Good Condition. Small tear on one side. Printed in red and black. Signed by Baskin and Keith. FROM THE COLOPHON: “John Woolman designed this dream to be placed at the end of his journal. Two years after his death, the Quaker editors deleted it in the First Edition of 1774. It is here printed from his Manuscript at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The woodcut by Leonard Baskin is printed from the block. 500 copies of this broadside, 50 of which are numbered and signed, were struck off at the Gehenna Press, Northampton, Massachusetts in March 1970. Copies 1-50 are signed by Keith and LB.” This is Number 43.

John Woolman was born in 1720. He was a Quaker and, at age 22, determined that

“slave-keeping was a practice inconsistent with the Christian religion.” He traveled widely, persuading others in his faith to abolish slavery. The practice ended within the Quaker faith by 1794.

Woolman kept a journal, published posthumously, that is prized for its clarity, humility and sense of purpose. It continues to be published today.

In Woolman’s dream, a hunter captures a live creature that is a mix of a fox and a cat. It is vicious with large claws and teeth. Community residents decide they need to find flesh to pacify the creature, and choose to hang an enslaved man (pictured in the upper right of the image) who is too old to do work. No one does or says anything to stop it. Woolman is horrified and distraught, but cannot get himself to speak. This dream, and the powerful image that Baskin created, is my antidote to complacency; my answer to Johnson’s and Baxter’s call. We must look injustice in the eye, if we are to overcome it. And then act. My UU Minister Nathan Detering (quoting Edward Everett Hale) frequently reminds us that, “we cannot do everything. But we can do something. And that something is never nothing.”

Book collecting is part of my “something” – my small effort to honor and share stories of inspiring lives, so as to inspire myself and others to help bring about a more just ordering of society.

2014

(20) STEVENSON, Bryan. Just Mercy, A Story of Justice and Redemption. New York: One World, 2015. Very good condition. Trade Paperback Edition.

This book is neither old nor rare. But it is a fitting end to my [Ticknor Prize] submission. I saw Stevenson give a talk recently and I was mesmerized. Right out of law school, he started representing prisoners on death row and, over the last 30 years, has done more to promote justice than perhaps anyone in recent memory. He is a mix of Cesare Beccaria and Andrew Hamilton. This man has spent his adult life fighting against inequality, injustice, abusive power, poverty and racism. And what has he learned? That “we are all broken by something.”

Many of the lives captured in my collection are broken in obvious ways (Sewall, Seneca, Sherburne, Otis, Wheatley, Woolman). The cracks in others are more hidden. But in every case, perhaps it is that very brokenness that has created the opening for profound action. As Stevenson writes, “our brokenness is also the source of our common humanity … [and] nurtures and sustains our capacity for compassion.“

The older I get, the more I appreciate that life is neither all good or all bad. Beautiful and terrible things happen, and we must learn to hold both at the same time. But through it all, we can engage our broken parts to inspire action, and to share our “common humanity” with each other. And that makes all the difference. What inspires me most about my collection is that it is a reflection of people working hard to do just that for more than 300 years.

Sources and Further Reading:

(1). Gookin. Breen, Louise A., Daniel Gookin, The Praying Indians, And King Philip’s War, A Short History in Documents. New York: Routtledge, 2020.

For a more general history of King Philip’s War: Leach, Douglas Edward, Flintlock & Tomahawk, New England in King Philip’s War. Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press, 2009.

(2). Selling of Joseph: https://www.masshist.org/database/53.

For background on Sewall: LaPlante, Eva, Salem Witch Judge: The Life and Repentance of Samuel Sewall. San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009.

For the Gehenna Press: The Gehenna Press, The Work of Fifty Years, 1942-1992, The Catalogue of an Exhibition Curated by Lisa Unger Baskin … Notes on the Books by the Printer Leonard Baskin. The Bridwell Library and The Gehenna Press: 1992.

For Sidney Kaplan: http://scua.library.umass.edu/kaplan-sidney-1913/

(3). Edward Sherburne: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Sherburne,_Edward;

Abednego Seller: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Seller,_Abednego

(4). Stowe, Harriet Beecher: Poganuk People. New York: Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1878, p. 174;

See also: Baker, Dorothy Z. America’s Gothic Fiction, The Legacy of Magnalia Christi Americana. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2007, p. 5.

(5). Addison. For virtue in Ancient Rome: Ricks, Thomas E., First Principles, What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How that Shaped Our Country. New York: Harper Collins, 2020, p. 5.

(7). Zenger. For a brief overview of trial: https://history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger/

For a comprehensive discussion: Kluger, Richard, Indelible Ink, The Trials of John Peter Zenger and the Birth of America’s Free Press. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

(8). For the Mather-Dummer connection: Cleaveland, Nehemiah, The First Century of Dummer Academy: A Historical Discourse, Delivered at Newbury, Byfield Parish. August 12, 1863, p.14.

(9). Montesquieu: Bergman, Matthew P., Montesquieu’s Theory of Government and the Framing of the American Constitution, Pepperdine Law Review, Volume 18, Issue 1, Article 3 (December 15, 1990)

(10). Beccaria. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library/detail/cesare-bonesana-di-beccariaon-crimes-and-punishments-1764

(11). Philis Wheatley: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Phillis-Wheatley;

Waldstreicher, David, The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley, A Poet’s Journey through American Slavery and Independence. New York: Frarrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023.

(12). MA constitution: https://www.mass.gov/guides/john-adams-the-massachusetts-constitution;

And four unique aspects: https://www.wgbh.org/news/2016/06/21/local-news/4-things-worth-knowing-about-massachusetts-constitution-which-236-years-old

(13) Another Jefferson-Leitch note: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-15-02-0287

(14). Isaiah Thomas. Bookplate: Brigham, Clarence S., Paul Revere’s Engravings. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society, 1954, p. 114.

Life of Wheeler: Obituary: William Augustus “Whizzer” Wheeler pressherald.com;

Background on Thomas: Shipton, Clifford, E., Isaiah Thomas, Printer, Patriot and Philanthropist, 1749-1831. New York: Printing House of Leo Hart, 1948;

And Lincoln, William, History of Worcester Massachusetts. Worcester: Charles Hersey, 1862 (pps. 240-246).

And: https://commonwealthmagazine.org/opinion/tracing-where-worcesters-grit-comes-from/

(15). Timothy Bigelow: History of Worcester Massachusetts, note (14),p. 223.

To collect and preserve: Burnside, Samuel M., Memoir of Isaiah Thomas, LL. D., in Archaelogia Americana, the Transactions of the American Antiquarian Society, (item 1)), p. xxvii.

(16). For the changing narrative of King Philip’s War over time: Lepore, Jill, The Name of War, King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

For “lion not telling giraffe story:” Washington, Harriet A., Medical Apartheid. New York: Harlem Moon, 2006, p. 8 (book discusses history of abusive medical experimentation on black Americans.).

(17). Harriet Beecher Stowe. For information about Eugene Field, II as forgerer: https://www.pbs.org/video/appraisal-forgery-eugene-field-jr-ca-1920-j7ymtj/

(18). For details about the Baxter sermon and the St. Mark’s service on November 23, 1963: http://stmarks.net/assets/pdf/Nov_24_2013_final.pdf (pages 14-24).

For the life of Baxter: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/william-m-baxter-episcopal-priest-who-preached-to-a-president-dies-at-90/2014/09/06/ad01fede-3071-11e4-bb9b-997ae96fad33_story.html

(19). John Woolman. For a brief video on the life of John Woolman: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqjCSGQtRUk

(20). For discussion of “brokenness,” see page 289. For information on the Equal Justice Initiative, created by Stevenson: https://eji.org

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

-Leonard Cohen